“Gray has much broader, more ambiguous, and more complex connotations, undefined, with different shades and tints. Reality is always complex. Not everything is black and white. Reality is gray─.”

Old and new, good and bad, black and white, past experience, knowledge and new findings, evolution and positive devolution, familiar and unfamiliar things—the author notes that our perception is always with and in these contrasts.

The author writes, “In particular, designers must move around in the world, deeply examining objects, environments, and relationships from different perspectives, which requires physical and mental movement. To do so, designers must observe objects and their evolution or devolution; they must also understand people, the environment, and the relationship between them.”

“Peace is the evolution of war. It can only happen once all sides have interacted and come to understand the complexity and diversity of humankind and human thought. War is all black, while peace is gray. Gray is a more natural and right answer for life and peace…. Peace is a product of design, just like anything else. It is a continual process that is alive and reactive. Designers and scientists have the power to improve this product to make it more durable and of higher quality. Changing the way we or the policy makers see, think, feel, and ultimately act, can make a significant difference in the design of peace in life.”

The core of Design x Science for Peace, by designers and only designers can testify.

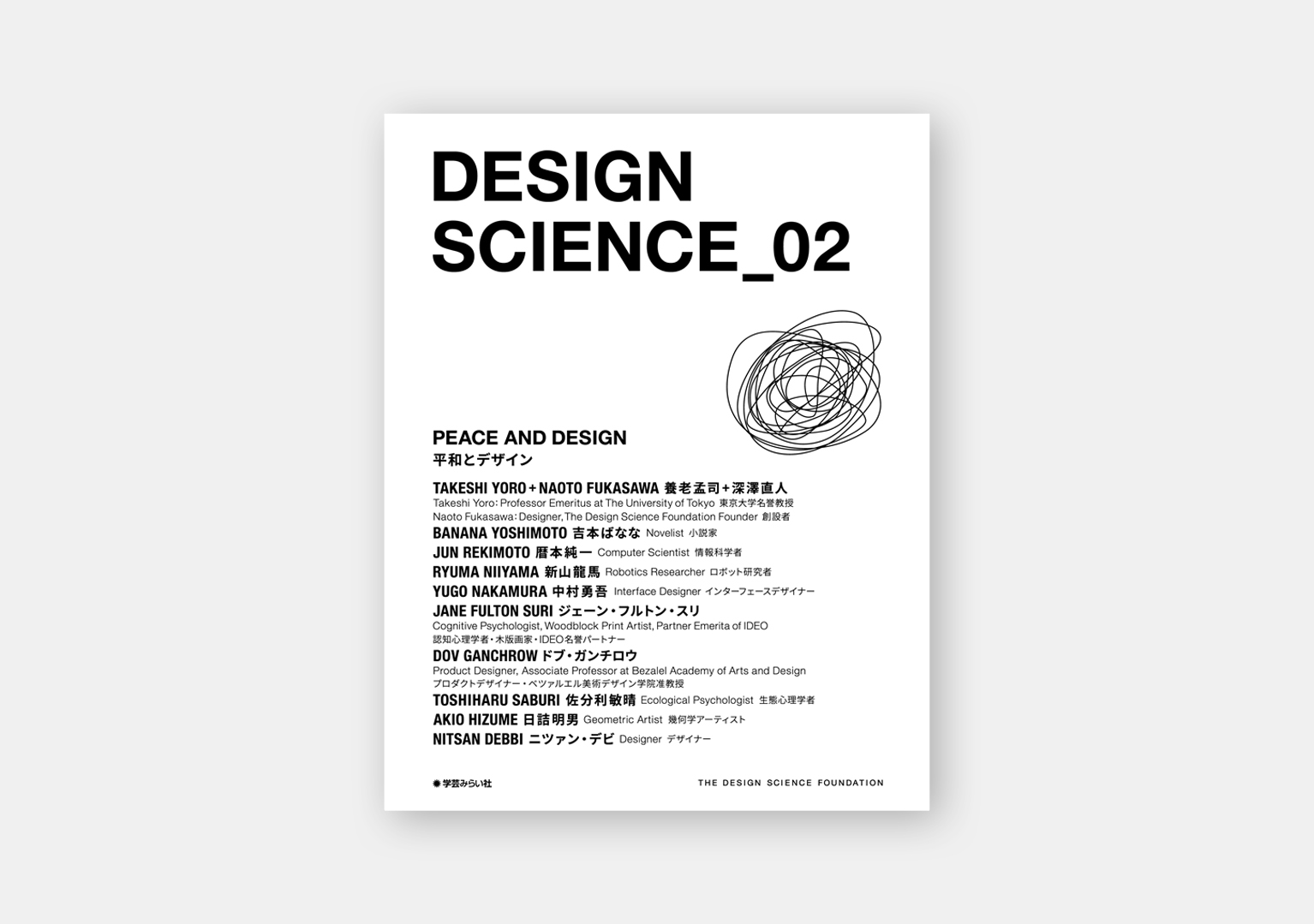

Nitsan Debbi

Designer

Debbi was born in 1982. She attained a B.A in Industrial Design in 2008 at the HIT (Holon Institute of Technology) in Israel, and a Master’s Degree in Industrial Design in 2011 at the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Israel. After completing her B.A, she started working at Keter Plastics. In 2011, she established Studio Bet with Liora Rosin, focusing on design exhibitions, product designs, and craft projects. In 2013, she moved to Japan after receiving a design research scholarship from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. She joined Naoto Fukasawa Design in 2015, and spent five years at the Tokyo office and since 2019 at the Tel Aviv office. She is a Lecturer faculty member and the newly elected Chair of the Industrial Design Department at the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design.

With an understated and human approach to objects, Debbi enjoys exploring various fields including furniture, lighting, installations, and exhibitions, and at the same time exploring the relations between design, culture and other disciplines, such as science and biology.